Penelope as Landscaper

Subscribe to Art Lies newslette

Copyright ©2010 ART LIES.

All Rights Reserved.

Issue 65

The Nature of Place: Land Art/Land Use

Land Heritage Institute

-

-Ariel Evans -

…if you went to Paris and dug up Claude Debussy, and you said, “Excusez-moi, monsieur, qu’est-ce que vous pensez de l’impressionisme?” he’d probably say “Merde” and go back to sleep. That’s not how the people who are doing it work.… You’re trying to find something that means something to you, that excites you, that gets your juices flowing.… What it’s called later by other people is useful. It’s easier to say “minimal” than it is to say “Steve Reich/Philip Glass/Terry Riley/John Adams/blah blah blah.” But that’s about it. And if you’re interested in this kind of music, then what you’re interested in is how these composers are different from one another. Therefore, for me, minimalism never existed—people existed.

—Steve Reich

Since the term “land use” covers so much—including how people have lived on the land for the entirety of human existence—it is not surprising that the Land Heritage Institute displayed many and varied approaches to the subject in its 2009 Art-Sci Symposium, “The Nature of Place: Land Art/Land Use.” This was the first such symposium at the LHI, a year-old “living land museum” situated next to a new Toyota plant south of San Antonio and atop geological strata containing evidence of 15,000 years of human occupation. Alston V. Thoms, in his presentation “Land Heritage Institute: Buried Landscapes and Ancient Land-Use History,” explained the history of the site. After people found Clovis points in the area, Thoms and his team dug thirty feet into the ground to find the cooking pits and other remnants of indigenous populations.

This intense and ongoing engagement with a section of the Medina River embodied speaker Lucy Lippard’s call for eco-art, that is, art that engages with the habitation and stewardship of land. Lippard, who spoke immediately prior to Thoms, posed eco-art in opposition to land artists of the 1960s. For Lippard, land artists were city folk traveling West, and using its landscapes as raw material for self-expression. Michael Heizer’s Double Negative, in this formulation, is touristic and picturesque, his marks into the cliffs a way of digesting sublime landscapes.

Yet Lippard’s attempt to name these eco-artworks with terms like “microlocality” doesn’t describe much. These namings are not, as Steve Reich says, “how the people who are doing it work.” Because of the multiple and diverse approaches to land use presented at the symposium, land use is difficult to write about: adjectives fail, and it’s harder to define land use after the presentation than it was before. I think it’s better to not try naming these practices. I hesitate at even using the phrase land use, since discussing landscape in the work of presenter Sandy Stone, for instance, is a stretch, albeit an interesting one. I think by labeling we risk closing down a plethora of possible meanings.

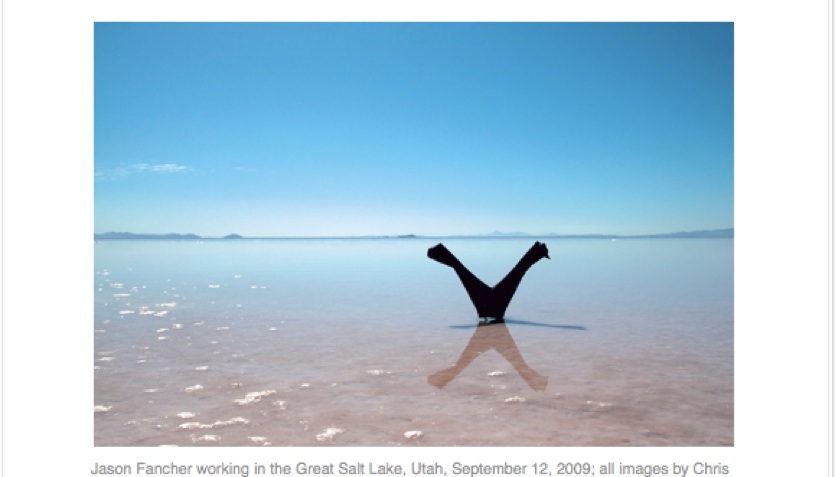

Exploring Spiral Jetty, Rozel Point, Great Salt Lake, Utah, September 11, 2009

Jose Villanueva filming Deer Man running across Interstate 10 near Cabinetlandia, east of Deming, New Mexico, October 14, 2009

Though it was a bit unexpected to find an archaeological dig exemplifying an artistic theory and critique, it’s not uncommon for science to mimic art, intentionally or not, a point made particularly apparent by the work of the Center for Land Use Interpretation (CLUI). CLUI, represented at the symposium by Eric Knutzen, undertakes a range of projects, from a database of images and descriptions of sites of land-use interest, to bus tours and exhibition trailers. Particularly stunning are their photographs of a Nevada missile test site—“America’s Eiffel Tower,” as I remember Knutzen putting it—with perfect circles cut into flat ground. CLUI hopes to reveal crucial structural aspects of America to which most of us have little access otherwise, while maintaining a rigorously objective view that avoids political affiliation.

Knutzen spoke of CLUI’s attempt to “frame in,” that is, to eschew conventional photographs of broad vistas free of human intervention and instead show the marks of human presence. It’s interesting that they attempt an objective interpretation of a given site yet take cues from the aesthetic vocabularies of conceptual art, a field widely considered as subjective exploration. There’s also not much specifically artistic in CLUI’s research-oriented methodology outside of their unclear criteria in determining sites of interest, and the fact that they get funding from arts organizations and present their work at art and architecture gatherings.

When Robert Smithson included snapshots in his Non-Sites, he made it clear that his photographs were not art but documents. No matter how often Smithson employed photography—indeed Gianfranco Gorgoni’s photographs of Spiral Jetty are iconic images now—Smithson insisted that art remain a palpable object. CLUI insists on this distinction as well; Knutzen maintained that their photographs functioned as a “window for you to look out into the land itself,” yet CLUI creates no palpable object. The object is the already-present site depicted in each image.

Sunday’s presentations offered more in terms of specifically artistic approaches. Joan Jonas gave an overview or her work, noting that most of it comes out of concerns with performance and ritual. Jonas traveled through the Southwest with Richard Serra and Robert Smithson back in the sixties or seventies, visiting land art sites and attending a Hopi snake dance. These travels played an unexplicated but powerful role in Jonas’ early videos where she explored how distance affects the viewing of space. When performers clap wooden blocks together in Song Delay (1973), for example, the sound and Jonas’ camera technique interfere with the viewer’s sense of space and distance.

Land art is becoming land use—clearly a number of the presenters, like Jonas, owe a large debt to earthworks titans like Smithson and Walter De Maria. Land art was really a bunch of people doing different things; its appearance in the works of people interested in land use revives its dynamic aspect. Land use is still unstable and shrugs off attempts at institutionalization, which can make it hard to study. Yet, as Stone emphasizes in her teaching at the University of Texas’ ACTLab, this instability keeps a field alive.

Stone, speaking after Jonas, presented work that re-maps conceptions of the individual and collective human body. For Stone, the physical and sexual are completely fluid: in one video she played of a performance in Europe, Stone re-mapped her clitoris into her palm and brought herself to climax. Stone’s fluid approach to the understanding of “body” and “nature” underlined the multidisciplinary approach of the symposium. For Stone, conceptions of the body are as situated and layered as conceptions of the land are for CLUI, Thoms and Lippard. While I don’t have enough space to talk about everybody, the main presenters never failed to amaze. The symposium was a raging success, and I hope Land Heritage Institute does it again.

Ariel Evans is a freelance writer based in Austin and is an Editorial Intern at Art Lies.